A basic issue when collecting, modifying, and sharing data online is whether that data is personally identifiable. A great example of how policy makers think about personally identifiable information is the HIPAA’s (Heath Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) “Privacy Rule”, which lays out rules for use — and notification to patients of use — of identifiable information. The problem is given sufficient storage, bandwidth, and computation, ultimately all information is going to be personally identifiable.

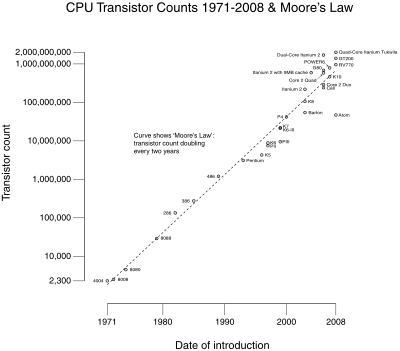

Thanks to Moore’s Law, storage, bandwidth, and computation are rapidly becoming sufficient. Backblaze offers unlimited online storage for $5/month. For less than the cost of a single machine, you can throw a substantial map-reduce job at Amazon Elastic Mapreduce to analyze staggering amounts of data. If you can get the data, you can store it and chew on it until you pieces start falling into place.

This also means that just about any piece of information you create — from your Twitter stream to your cell phone’s geo reporting — become subject to Metcalf’s Law, creating value from network effects. Metcalf’s Law is, of course, a heuristic about communication networks, but the principal of network effect — where the addition of one additional good or service generates additional value for everyone in the network — clearly applies to networks of information as well. More data and more analysis create more valuable data sets with more interesting correlations to explore.

This is positive reinforcement at its best (or worst). New correlations create new ways to examine old data and better filters to apply to new data, generating even more value and knowledge.

This virtuous cycle has two interesting outcomes. The first is the breakdown of the old distinctions between meta information and information. Meta information — or information about information, often called metadata — has historically been structured data used to reduce search costs. Effectively lossy, informational compression. Think index of a book or the stats line on a baseball game. Computing the metadata takes time, but once computed becomes a cheaper (faster) way to get some information.

What Google has shown is that with sufficient computation, meta information can be context dependent and recomputed as needed. Compare using the index to look up key information in a book versus googling for it. Or, standard baseball stats versus sabermetrics. This last example is particularly important, as it also illustrates how standardizing on meta information — the usual baseball statistics of RBIs, homeruns, etc — blinded baseball from looking more deeply into how to really differentiate player performance. Sufficient computation means constantly digging into the data in order to find new information, new order, and new ideas, rather than simply finding one viewpoint and sticking to it.

But this flexibility and the value of increased analysis may come at the price of all information ultimately becoming personally identifying information.

Currently, a basic assumption is that we know a priori what data is going to be personally identifying. Worse, it is assumed that it is possible for a consumer, a user, or a business to know the difference. This may have been a safe assumption in the past, but it clearly is not today.

Consider the Netflix Prize, where Netflix crowdsourced a better prediction model for movie ratings. In order to provide data to prize participants, Netflix released 100 million movie ratings from 480,000 customers. Customers were identified by a unique user ID, so Netflix clearly felt safe releasing this data. After all, with movie ratings linked back to a random number, this obviously wasn’t personally identifying, right?

Wrong.

Two University of Texas researchers, in Robust De-Anonymization of Large Sparse Datasets (pdf link) demonstrated that by comparing reviews to public sources, such as IMDB, it was possible to identify users in the Netflix data. Unsurprisingly, a user who thought her rentals were private is now suing Netflix.

Nor is this new, as we saw when AOL released “anonymized” search engine logs.

Suddenly, the information virtuous cycle gets even more powerful, if less virtuous.

Any information that is created and stored is likely to eventually become personally identifying. Thanks to Moore’s Law, more and more of our lives are generating bits that are stored somewhere. Thanks to Metcalf, anyone with access to the information can create value by collecting and analyzing that information, ensuring that anyone who can afford to, will. Again thanks to Moore, analysis and storage is cheap enough to be available to almost anyone, not just governments and large businesses.

So, the limit case is that everything we do is stored and linked back to us. Sounds like either the Panopticon or David Brin’s transparent society. Or both.

Current trends and incentives seem to make that limit case inevitable.

What to do about it in a later post.